Overview

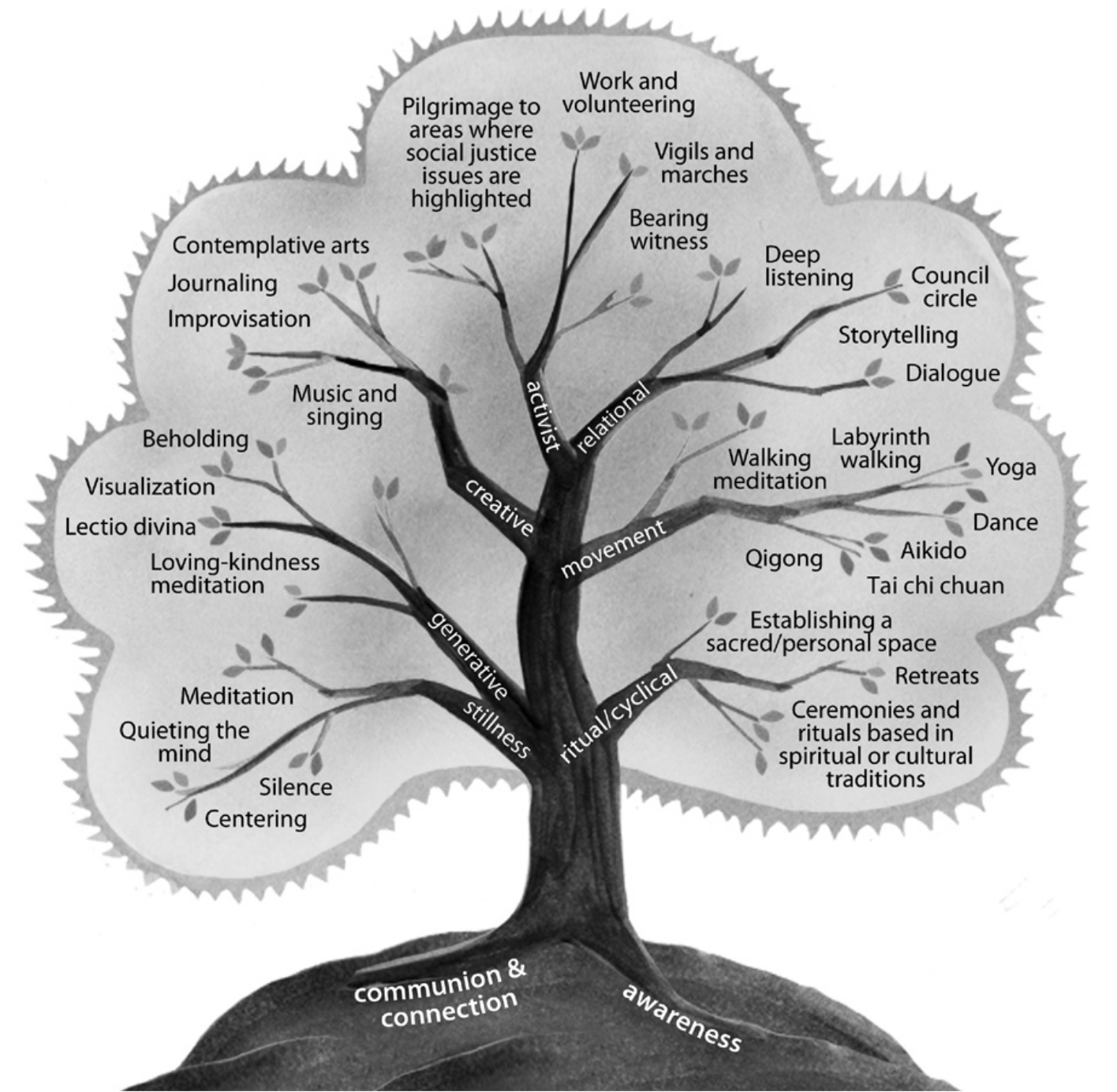

Contemplative practices can refer to a whole range of practices, from personal introspective practices to relational practices like dialogue to movement practices like yoga or dance. I like the visual of the tree of contemplative practices from the [Center for Contemplative Mind in Society] (shown below). The roots of the tree are awareness and communion/connection. Ultimately, contemplative practices are rooted in the subjective, something which we often overlook in modern life.

I’ve come to view the tapestry of contemplative practices as a laboratory for self-inquiry. A contemplative practice, in my view, is any practice that brings greater understanding of oneself and of one’s interbeing (to use a phrase from Thich Nhat Hanh) with the world. In any contemplative practice, the two roots - awareness and connection - are in conversation.

Meditation is often considered a contemplative practice. One issue with this way of categorizing meditation is that many forms of meditation are non-conceptual. Though this may muddy our definitions some, I prefer to think of meditation practices as practices that examine the context of our experience and contemplation practices as those that examine the contents of our experience. Though I doubt any hard division can be made between these two practices, it’s important to recognize that many approaches to meditation are explicitly not about thinking our way to some realization.

I prefer a dialectic view of the relationship between meditation and contemplation. In this view, meditation is like taking off your glasses, looking at the lenses, maybe trying to wipe them clean. Contemplation, on the other hand, is like putting your glasses back on and seeing how your vision of the world (and yourself) has changed. Whether we literally wear glasses or not, we all wear metaphorical glasses in the sense that our experience of reality (regardless of our metaphysical beliefs) is mediated by our senses and the interpretive work that our brains do with that sensory data.